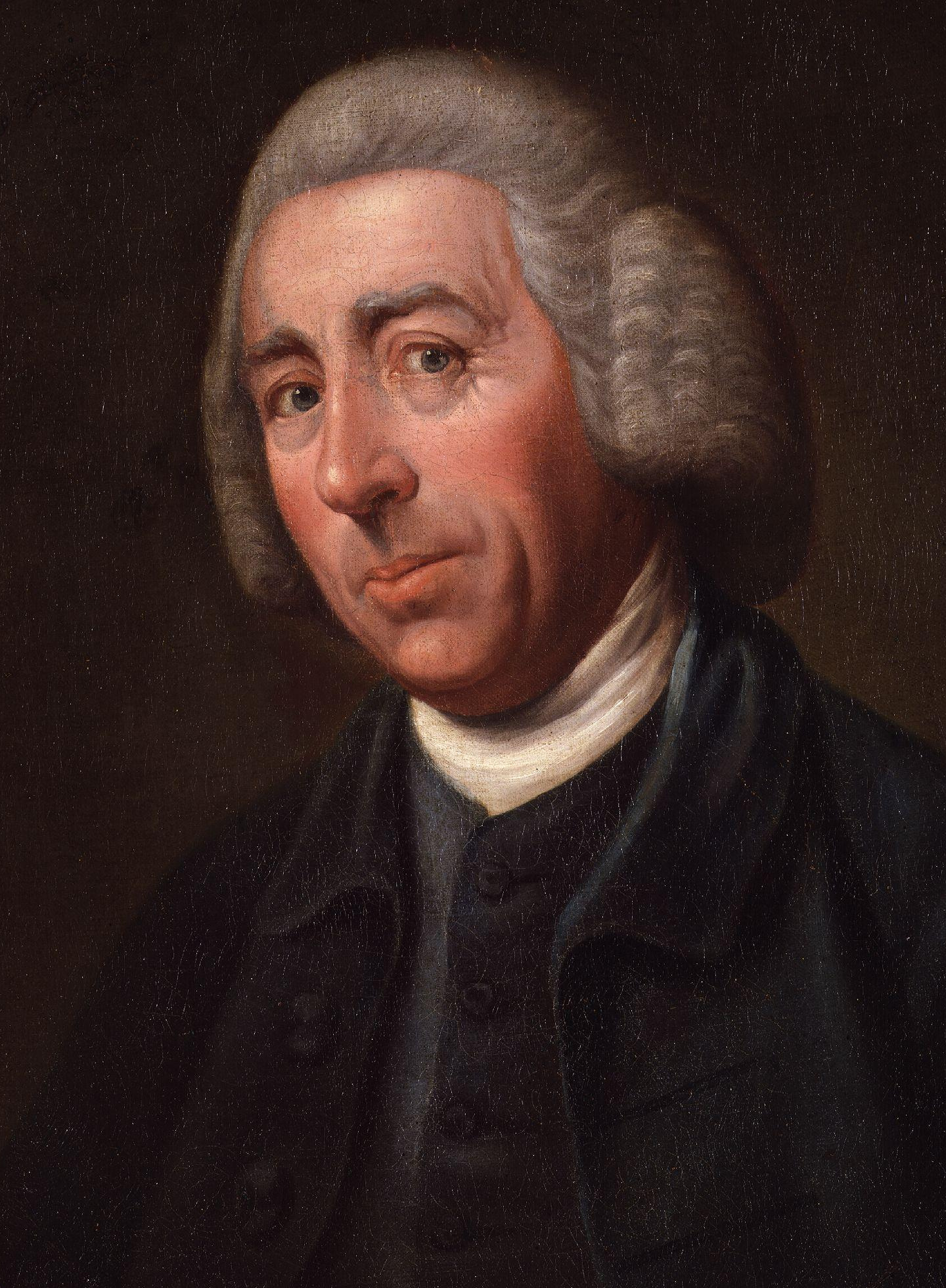

_Brown_by_Nathaniel_Dance,_(later_Sir_Nathaniel_Dance-Holland,_Bt)_cropped.jpg) |

| Lancelot 'Capability' Brown (1716-1783) |

Now then. Lancelot 'Capability' Brown is one of the most contentious designers in British garden history, and its often a case of love him or hate him. He is often accused of destroying so many of the English Renaissance gardens of the 17th century. Considering that the Civil War had taken a hefty toll of gardens and that Brown was the third in a line of great landscapists and oftentimes worked on landscapes they had, I am not sure how far this accusation sticks.

And he is occasionally accused of designs that resulted in the displacement of villages and villagers. This is certainly true, but the Enclosure Acts were far more pernicious than the mild-mannered Brown.

|

| Brown's landscape at Montacute: more natural than nature! |

I am sure you can see by now that I fall into the former category and think that Brown's work was genius. To be able to envisage how a mature landscape should look at its peak - 200 years into the future - takes vision; and there is also something humbling about Brown and his work for he must have know that he would never live to see one of his designs reach maturity.

|

| Brown's landscape at Blenheim - perhaps his finest. |

And for my money he was also the first Modernist. For if we apply the maxim 'form follows function' then that is exactly what his designs achieved. They were the 'natural' English landscape perfected, and thus performed their artistic function, whilst simultaneously demonstrating that the owner was at the cutting edge of fashion. Yet they were also productive and yielded an income and also met the requirements of countryside recreations.

|

| Chatsworth set within Brown's landscape |

So, may I introduce you to the new blog Lancelot Capability Brown which is dedicated to proselyting about the man, his work and celebrating the forthcoming tercentenary of his birth.

You can also follow Lancelot on Twitter: @Brown2016