|

| Blenheim Palace (from 1764) is often considered Brown's finest work |

Next year marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Britain's greatest landscape designer, Lancelot 'Capability' Brown. Certainly his work was the apogee of the eighteenth-century English landscape garden, and I still maintain that if one applies the two Modernist maxims of 'Form follows Function' and 'Less is More' then Brow was not only the first Modernist landscape designer but also by far the most successful.

However in the 232 years since his death poor old Brown has come in mor more than his fair share of stick. In fact vitriol would be a more accurate word. A destroyer of formal gardens, a displacer of villagers are but two of the accusations used to beat him with.

And to our national shame Brown has been deliberately ignored or exorcised from various celebrations of British gardening and garden history. So thank goodness that he is now getting some of the much credit he is due.

|

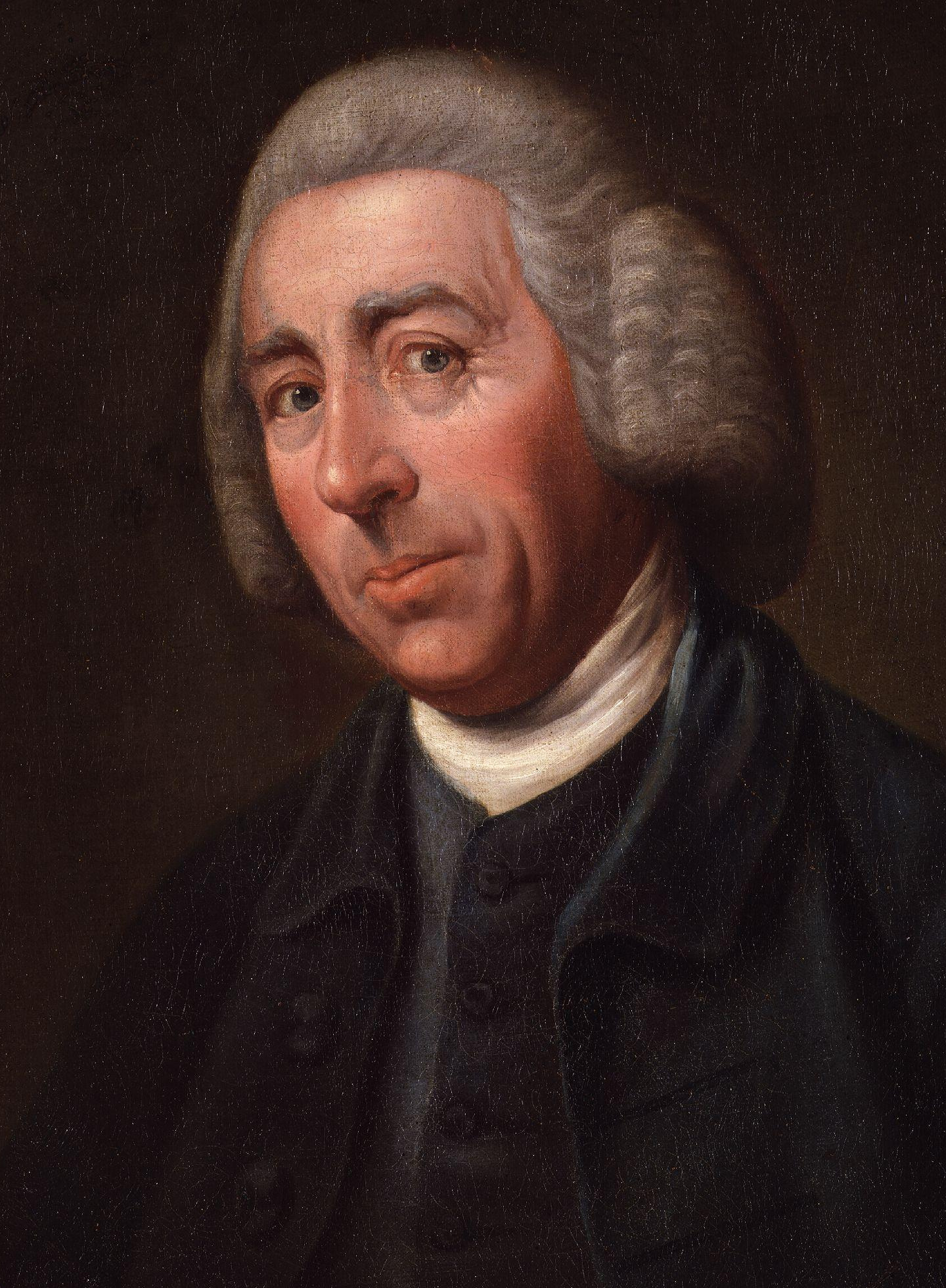

| Portrait of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, c.1770-75, Cosway, Richard (1742-1821)/Private Collection/Bridgeman Images. |

Today sees the launch of the 'face' of the Capability Brown Festival 2016 . The portrait of the affable-looking chap himself is by Richard Cosway, probably between 1770 and 1775.

The Festival has been has been funded by a £911,100 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund with the wider project worth in the region of £1.7million. Much of this represents match funding, and funding in kind, from the Festival’s partners and supporters.

The website has a wholæe host of information about events, projects etc., etc, and here too you can sign up for the latest news.

There are more than 250 sites associated with Brown across England, with a small handful in Wales. They range from small private gardens to larger country estates, and include 12 public parks, some schools and hotels. Many are managed by members of the Historic Houses Association, the National Trust, and English Heritage.

To find an example of Brown's visionary genius near you, check out this interactive map.